“If a tree falls in a forest and no one hears it, does it make a sound?” Is there a sound if no one can hear it? George Berkeley, who first formulated this thought, argued that objects exist only if perceived. Therefore, for Berkeley, the answer was clear: if a tree falls in a forest and no one hears it, it does not make a sound. Following the same logic, we might ask: “If the results of a clinical study are not published, do the resulting findings exist?” The results of a clinical study include the data collected and the analyses performed during the experimentation, representing the “building blocks” of information, but this information only becomes meaningful when shared. The effective publication (sharing) of clinical study results is thus an integral part of scientific research and helps generate new hypotheses and better guide clinical practice. A well-planned and well-written “Results” section is a valuable tool for communicating, clearly, concisely, and objectively, the innovative aspects and nature of the information emerged from the study, guiding the reader through the questions investigated in the “Materials and Methods” and laying the groundwork for interpretation and critical analysis in the subsequent section (“Discussion”).

The “Results” are therefore a fundamental part of any scientific article; in fact, they are the very reason for writing an article: the presentation of new and, ideally, significant facts. To begin writing, the first step is to select and establish which results to present—specifically, which results are relevant to the clinical question posed in the introduction, regardless of whether they support the hypothesis. The “Results” section does not necessarily need to include every result obtained or observed; however, it is important that there is correspondence with what is outlined in the “Materials and Methods”: for each method (what was done), there should be a corresponding result (what was found), and vice versa.

The “Results” section should describe in a logical order what was done and found, the frequency of occurrence of a particular event or result, the quantities of observations, and the causality (i.e., the relationships or connections) between the observed events. Results can be structured chronologically, from general to specific, from most important to least important, or grouped by topic/study groups or by experiment/parameter measured.

Generally, the Results section covers three areas of interest (demographic and baseline data, efficacy, and safety) and includes the following elements:

- A very brief introductory context that reiterates the research question and helps understand the results.

- Information on data collection, recruitment, and/or participants.

- A systematic description of the main results, highlighting the most relevant findings.

- Other relevant secondary results, such as secondary outcomes or subgroup analyses.

Ideally, the “Results” section should present itself as a dynamic interaction between text (which tells the story), non-textual or visual elements (which summarize the evidence and/or highlight the main results), and statistics (which support the information). The mode of presentation should aim to optimize understanding of the data, and the choice of format depends on the level of detail to be presented.

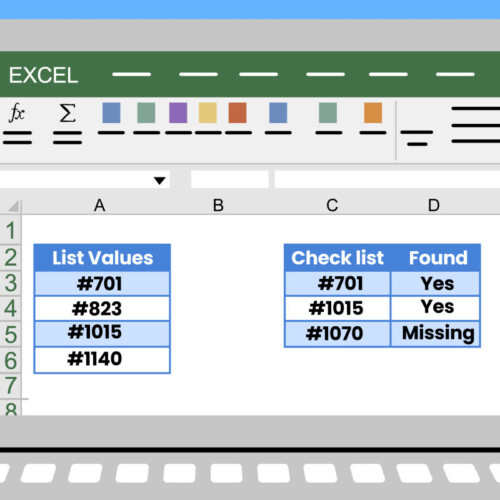

Using non-textual elements such as figures, graphs, tables, etc., allows authors to summarize a large amount of data compactly, organizing and visualizing the data more clearly than text, enabling the reader to grasp the information more easily and quickly.

As a general rule:

- Tables are used to communicate exact values, providing a concise overview of various results.

- Graphs and diagrams are used to depict trends and relationships, providing immediate visualization of the main results.

- Non-textual elements capture the reader’s attention; thus, it is crucial to pay attention to their graphic presentation, ensuring they are informative, comprehensive, and easy to understand.

In this section, the results of the main methods of descriptive and inferential statistical analysis are finally presented. Statistical analyses must report data in a way that allows the reader to assess the degree of experimental variability and estimate the variability or precision of the results.

We conclude with a brief series of tips and suggestions for structuring a good “Results” section and effectively communicating the innovative aspects of your study: only effective communication can best highlight the obtained results.

Do’s | Don’ts |

|---|---|

Select relevant data/results. | Report all results, including those unrelated to the main hypothesis/objective of the study. |

Organize the “Results” section logically. | Discuss and interpret the results. |

Match each result with the corresponding evaluation/measurement method. | Report similar results in both textual and non-textual elements. |

Structure the results chronologically, from general to specific, from most important to least important, or grouped by topic/study groups or by experiment/parameter measured | Present raw data. |

Use a combination of text, tables, and figures. | Present data without units of measurement. |

Describe relevant data/results concisely and objectively. | Present inaccurate, disorganized, and unclear tables/figures. |

Quantify the results using statistical significance values. | Focus solely on results related to the main hypothesis/objective of the study. |

Adjust the text to the journal’s style |

Sources

Bahadoran Z, Mirmiran P, Zadeh-Vakili A, Hosseinpanah F, Ghasemi A. The Principles of Biomedical Scientific Writing: Results. Int J Endocrinol Metab. 2019 Apr 24;17(2):e92113. doi: 10.5812/ijem.92113. PMID: 31372173; PMCID: PMC6635678.

Lövei, Gábor. (2021). Writing and Publishing Scientific Papers: A Primer for the Non-English Speaker. 10.11647/OBP.0235.