We have reached the final article in our series on the structure of a clinical article.

To briefly summarize what we’ve covered, a clinical article begins with a section called “Introduction”, which frames the clinical context in which the study was conducted and describes the reasons for undertaking it.

The following section, “Materials and Methods”, specifies how the study was conducted, providing the reader with all the necessary information to assess the adequacy of the research methodology as well as the robustness of the reported results.

Next, we looked at the “Results” section, which presents the data collected and the analyses performed during the clinical study. Tables, figures, and statistical analyses are integral parts of this section, guiding the reader through the relevant results related to the questions and hypotheses posed in the introduction.

In the “Discussion” section, the meaning of the collected results is described.

Now let’s explore the fourth and final section of a scientific article: the “Conclusions.”

The “Conclusions” Section of a Clinical Article

The recency effect is a cognitive bias that leads individuals to remember the most recently received information and unconsciously attribute more value to it. This is why knowing how to write the “Conclusions” of a clinical article is important. An effective concluding section offers the opportunity to leave a lasting impression on readers by providing a clear interpretation of the results, thereby reinforcing the overall integrity of the study.

This section is the opposite of the “Introduction,” not only in its placement but also in its structure. The introduction generally follows a funnel format, moving from the general to the specific.

The “Conclusions” adopt an inverted structure, beginning with the key points of the research and ending with a general and relevant statement that encourages readers to reflect and challenges them to act based on the new knowledge gained.

While the “Introduction” opens a dialogue with the reader by defining the research question, the “Conclusions” convey a sense of closure and completeness, emphasizing the implications and significance of the study.

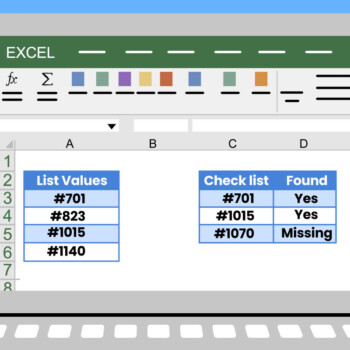

Below is our checklist containing some tips and common pitfalls to avoid in ensuring the effectiveness of the “Conclusions.”

Restate the research question.

Begin by clarifying your objectives and reiterating the main points of your thesis. Remind the reader of the study’s importance, presenting it in a way that differs completely from the Introduction.

Summarize the main results.

Keep in mind that the “Conclusions” section is not simply a summary of the paper, as it goes beyond merely repeating the initial thesis and obtained results. Instead, it offers a synthesis that places the main results in a broader context and explains their importance and how they contribute to the state of the art. Shift your focus from specific details to the overall picture of the research.

Avoid generic opening phrases.

Avoid starting your “Conclusions” with generic phrases like “In conclusion,” “In closing,” “In summary,” etc. While this may serve as an effective transition in oral presentations, it can be redundant in a manuscript. Be direct.

Explain the implications of the results.

Discuss how the results contribute to enriching the relevant research field and suggest potential theoretical implications and practical applications.

Identify study limitations and suggest future research.

Point out any limitations, deficiencies, or weaknesses in the study and propose ideas and recommendations for future research, including areas where further investigation is needed.

Use a concluding statement.

End with a strong statement that ties together the main points and emphasizes their significance. Ensure the final paragraph conveys a sense of closure to this “clinical narrative,” providing a clear and comprehensive message without leaving room for doubt.

Use clear and concise language.

The “Conclusions” should be engaging, concise, and leave the reader with a clear understanding of the research. Avoid technical jargon or overly complex language; instead, choose accessible language for a wide and diverse audience.

Avoid introducing new information.

It’s important not to introduce new information, as this can confuse readers and undermine the entire argument. Stick to summarizing the main results, discussing implications, acknowledging study limitations, and suggesting future research. Don’t ignore “negative” results.

Report and transparently interpret any “negative” or inconsistent results.

If omitted, these could invalidate the main message.

Avoid ambiguous conclusions.

If the “Conclusions” section is ambiguous, it may give the impression that the study is incomplete, inadequate, or fundamentally flawed. Write the “Conclusions” with direct language, taking a firm stance.

Here’s our take-home message: the “Conclusions” focus on the significance of the study’s results and their potential implications. A well-founded conclusion can enhance the likelihood of the manuscript being published in industry journals and maximize its impact in the relevant research field.